A statistic that is changing the face of road safety technology. Frances Cook reports on a range of anti-sleep technology coming to the fore through the ability to not only wake up drivers but stop them from falling asleep in the first place.

According to the ‘Think!’ campaign, which is run by the UK’s Department of Transport, approximately 20% of accidents on major roads are sleep related. This is a problem experienced worldwide.

In the US, a ‘Sleep in America’ poll found that 60% of adult drivers (around 168 million people) have driven a vehicle when feeling drowsy and more than one-third have actually fallen asleep at the wheel – in fact a shocking 13% fall asleep at the wheel once a month.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates that 100,000 police reported crashes in the US are the result of driver fatigue, which results in 1,550 deaths, 71,000 injuries and $12.5 billion in financial losses.

“People think they can judge the precise time they are too tired and don’t realise that ‘drowsy driving’ is a serious danger,” said David Cloud, CEO of the National Sleep Foundation. “They don’t know that it’s possible to fall into a 3-4 second micro sleep without realising it.”

Wake up and drink the coffee

Blinking frequently, difficulty remembering the last few miles, having trouble keeping your head up, turning up the radio, opening windows, minor steering errors and drifting off-line are all signs that a driver should take a break from the road.

The National Sleep Foundation recommends having a good night’s sleep before driving, taking a break every 100 miles or two hours or consuming caffeine. But often the driver is not aware of how fatigued they are or they simply ignore their body’s own warning signals in favour of getting to the destination more quickly.

Until relatively recently the only technology available on the market to help drivers combat fatigue was based around waking the driver up. Products, like the Nap Zapper and the Doze Alert resemble a hearing aid and are placed behind the driver’s ear to detect head movement, so if the driver’s head tilts forward as the driver falls asleep the device will beep, waking the driver so he or she can take appropriate action.

While these products wake up the driver they do not assist with preventing the driver falling asleep in the first place. Over the last few years research into technology that will alert the driver of their drowsiness before they fall into a sleep state has developed a new range of solutions.

Camera tracks head movements

Researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Media Technology IDMT in Ilmenau, Germany, presented an Eyetracker system at the Vision trade fair in Stuttgart in 2010 that tracks a driver’s eye movements.

Using cameras – with lenses just three to four millimetres in diameter – the system follows the driver’s eyes when they turn their head.

The commercial version is said to be about half the size of a matchbox and can be mounted behind the sun visor and on the dashboard in any car.

“Since the Eyetracker is fitted with at least two cameras that record images stereoscopically – meaning in three dimensions – the system can easily identify the spatial position of the pupil and the line of vision,” said Professor Husar of the IDMT.The system is designed to issue a warning before the driver has a chance to fall asleep.

Manufacturers’ solutions

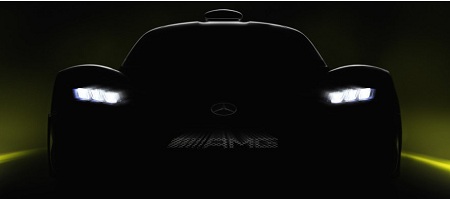

Drivers cannot however buy this technology off the shelf and more intuitive anti-sleep devices are only available depending on the type of car you choose to buy. Manufacturers such as Mercedes, Volvo and Ford, among others, have all developed devices that detect reduced driver concentration.

Attention Assist from Mercedes creates a profile of the driver’s driving style that is compared with feedback from sensors. Minor steering errors that the driver makes and corrects are recorded by the system and then checked against other data, such as how long the driver has been driving and external influences such as side wind. It will then issue a warning if evidence shows it is time for the driver to take a break.

Driver Alert Control from Volvo steps in when the driver is doing 65mph. The device monitors the car’s movements and assesses if it is being driven in a controlled way. “We do not monitor human behaviour – which varies from one person to another – but instead the effect that fatigue or decreased concentration has on driving behaviour,” explained Daniel Levin, project manager for Driver Alert Control at Volvo Cars.

Ford’s Driver Alert comprises a small camera that is trained to identify road lane markings and is connected to an on-board computer. When the driver loses concentration and makes corrective steering inputs, the system will pick up on this. “Let’s imagine the driver is tired, their concentration levels start to drop and the vehicle starts to drift from side-to-side,” said Ford engineer Margareta Nieh, who helped develop Driver Alert. “The software will detect this change in the vehicle’s behaviour, triggering a two-stage warning process.”

Anti-sleep device to change behaviour

But what if you do not own one of these high-end models with such a system? This is the position that Danish entrepreneur Troels Palshof found himself, in after falling asleep at the wheel after a late meeting approximately five years ago. Not able to find anything intelligent on the market to help, he started to develop his own device – now known as the Anti Sleep Pilot – which has already become so popular with drivers worldwide it can be bought on Amazon or downloaded as an app.

Palshof wanted to invent a system that was not based around a fatigued driver already making critical errors. He sought to create a revolutionary device that would take the individual driver profile into account and warn the driver when a break was necessary, but that would also change the behaviour of the driver over time.

“It is all about active prevention, changing people’s behaviour, active security and active safety,” said Palshof, CEO of Anti Sleep Pilot.

The system uses three different types of information in order to assess the driver’s concentration levels, so that a break can be suggested before driving mistakes start being made.

The first is a personal risk profile determined through the driver taking a short questionnaire. The second is your fatigue status before the trip – the driver enters information for eight relevant factors, such as amount of sleep in the last two to three days and how long the driver has been awake for.

The third is data from your driving that Anti Sleep Pilot registers via built-in sensors, such as the time of day (accidents from driver fatigue are more likely to occur at night or during the afternoon). In total, more than 26 scientifically identified factors are used.

Throughout the drive you receive alertness maintaining tests at 10 to 25 minute intervals, depending on your risk profile. Your reaction time to touching the top of the device on the dash is recorded against your personal profile and fatigue level.

If the driver’s concentration levels dip, the device will give audio and visual signals so the driver knows it is time to take a ten-minute break.

“Of course there’s no solution that can solve the problem if, say, a driver hasn’t slept for two days, but from a scientific point of view, if you get some fresh air and do something else, ten-minutes at the right time is enough,” said Palshof. “Too late and you will be sleep deprived and it won’t help you – at the right time it will have a huge impact.”